How Does Moral Progress Happen?

Part 1: The ideas, faith, and markets that made slavery anathema

When I was growing up, President Barack Obama would not endorse gay marriage, possession of marijuana meant a felony charge, to be racially “color blind” was a virtue, and the federal government tortured suspected criminals with impunity. In a few swift decades, public opinion across these issues—especially among “polite society”—has completely shifted.

Moral change is fascinating—the sudden or gradual redrawing of our moral preferences, norms, and practices in novel or even opposite ways. Nowhere is this more stark than on the issue of slavery.

Slavery is as old as humanity. Institutionalized by warfare, markets, religion, and cultural practice for 11,000 years, slavery was perpetuated and suffered by nearly every people group across every time period, rendered as normal a practice as paying taxes. We last know of slavery in one of its worst forms—the 400-year-long transatlantic slave trade that abducted, subjugated, and exploited Africans throughout the Americas. At the time of this enterprise—like every other time in human history—pro-slavery sentiments were widespread, usually justified with brazen racism.

Yet in the span of just 100 years, this millennia-long moral norm was upended. The practice was banned across most of the world, both through abolitionist movements and legal decrees. Consider the magnitude of that change: 11,000 years of social practice and moral consensus obliterated, relegated to a tale of premodern savagery, all in 100 effective years. That’s as groundbreaking as the invention of electricity or the internet.

From women’s suffrage to civil rights revolutions, history is written with many such bizarre examples of moral awakening. Moral philosophers theorize it as evolutionary, teleological, economic, cultural, or religious, but no one can truly ascertain how, why, or when it might happen. Still, we are all working to influence society’s conscience in one direction or another.

“Moral progress” means different things to different people. I’m a moral objectivist, meaning I believe in a universal good and evil independent of our preferences, and that it’s incumbent on us to discover and adhere to it. Some institutions and practices align us with moral good, and others—like slavery—do the opposite. I think humanity has made impressive gains towards “goodness,” but I don’t think all our moral changes necessarily indicate “progress.” While I celebrate gains in human rights and the general decline of violence, I’m less than pleased with the fruits of the sexual revolution or radical individualism. Most will agree that human morality has seasons of progress and regress, even if we disagree on what.

Watching numerous waves of moral change on the problem of American racism, I’ve long wondered if and when Indian society will similarly shame the practice of caste out of public life. The great Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s famous words, “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice,” promise hope for the afflicted—but was he right? And how do we know when the “bending” is happening?

The Power of New Ideas

Moral revolutions are almost always precipitated by novel moral ideas. It’s when a few thoughtful people derive new concepts about what we ought to value differently, and persuade the rest of us. The now banal idea that “all men are created equal,” for example, was hardly self-evident, as America’s Founders alleged. It had to first be presented as an idea and agreed upon—and further refined and worked out for centuries to come.

The most significant instance of moral innovation may have happened during the Age of Enlightenment, when notions of autonomy, justice, freedom, and dignity were redefined and popularized. These replaced prior honor codes and religious dictates, laying the foundation for an entirely new, rights-based order that spelled inclusion and dignity for many groups in centuries to come. The effects didn’t sink in immediately, however; the savagery of slavery, for example, paradoxically expanded and intensified alongside these changes.

The promulgation of new ideas is probably the most popular approach to moral change, even today. Many of the novel concerns of our era—racial equity, gender identity, environmental concern—are premised by academics and activists as moral convictions for us to adopt. And reliably, they encounter pushback. New moral demands elicit an “ugh” response from many, being perceived as obnoxious, unreasonable, or judgmental (consider the average PETA demonstration, for example). That’s hard to overcome, but social psychologist Jonathan Haidt argues people can be persuaded of moral change by appealing to their “moral foundations”—the deep instincts of conscience, like fairness, liberty, and sanctity. This tends to happen within another key lever of moral change: religion.

Sin, Salvation, and Slavery

The 17th century abolition of slavery was largely brought about by the religious convictions of Quakers and other Christians, who saw all human beings as being created in the image of God. The irony: their moral imperatives departed from mainstream Western Christianity at the time, which read the Bible as condoning and promoting slavery.

In his magisterial account of Western slavery, historian David Brion Davis argues that the religious idea of sin—both individual and collective, even national—was central to slavery’s justification and ultimate abolition: “Men could not fully perceive the moral contradictions of slavery until a major religious transformation had changed their ideas of sin and spiritual freedom; they would not feel it a duty to combat slavery as a positive evil until its existence seemed to threaten the moral security provided by a system of values that harmonized individual desires with socially defined goals and sanctions.” The blessing and curse of religion is that it possesses unparalleled authority to define good and evil, and motivate the requisite behaviors towards both.

This capacity to affect moral changes is why political agendas often latch onto religion or utilize religious themes. Anti-slavery advocates like William Wilberforce regularly invoked Britain’s national “Christian” identity—along with Christian theology about God, sin, and dignity—to argue for abolition. Philosopher Kwame Anthony Appiah writes that Christian doctrine on murder was pivotal in eliminating the honor code-era practice of dueling to settle disputes. Tracing the second-order consequences of religious dictates, philosopher Joseph Heinrich goes as far as to argue that the church’s ban on cousin marriage is the reason for both economic and moral progress in the West: incest prohibitions forced families to mix more, leading to greater social mobility, leading to greater economic development, leading to greater moral impartiality and universalism. In this butterfly effect, though, it’s actually economic development that begets the largest ripples of moral change.

The Invisible Hand

To that end, some philosophers argue that moral inclusivity only flourishes in societies with favorable economic and social conditions. I’m less convinced of this theory; to once again take the example of slavery, it’s obvious that economic prosperity can coincide with moral depravity and evil. Philosophers like Peter Singer argue that modern wealth blinds people to their duty to reduce suffering.

But through what economist Adam Smith called "the invisible hand," markets also have the subversive capacity to achieve morally ideal outcomes at scale—even if by means of self-interest. Some historians even view the abolition of slavery as more plausibly motivated by economic incentives than virtue. Many American Northerners—including, potentially, President Abraham Lincoln—opposed slavery for fear that “slave power” enjoyed by slave owners gave them a disproportionate advantage over free white farmers using free labor. This concern may have trumped any sympathy for the slaves themselves. This isn’t universally true, however—Great Britain stood to gain nothing from abolishing one of its most profitable enterprises.

In another case, the sexual revolution of the 1960s—which indicated all sorts of moral changes (some for better, some for worse) in gender roles, sexual norms, the institution of marriage, family structure, and so on—was itself catalyzed largely by oral contraceptives, invented in the 1950s. In this case, it was scientific advancement and commodification that catalyzed the rapid liberalization of society—not moral or spiritual claims.

New ideas, religious reformations, and markets are just a few tested levers for moral change, but how well do they stack up against the monstrosity of caste?

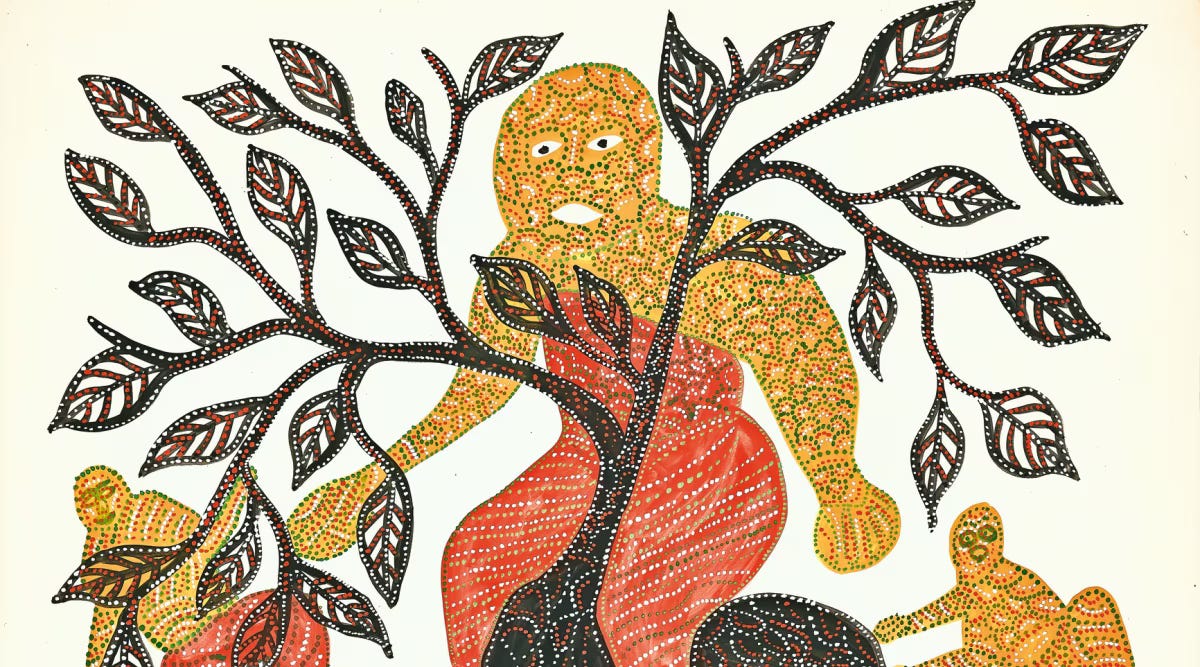

Caste Eludes The Arc

On paper, India checks many of modernity’s moral boxes. It’s a democracy. It is, in theory, secular. But this ancient moral pathology—caste—has not only survived modernity, but adapted to it. Even as Indian corporations embrace progressive protections around race, gender, sexuality, and disability, caste is conspicuously absent. Many young Indians express outrage over racism, imperialism, and patriarchy—but remain silent on caste. Caste has remarkably evaded every wave of moral renovation in its path.

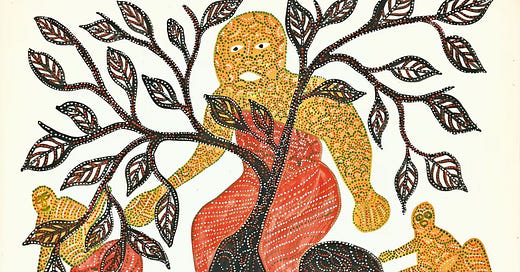

The prophets of the anti-caste tradition all advanced new or renewed ideas of morality—from Buddhist reclamations of dharma and karma to Enlightenment-style principles like liberty, equality, and fraternity. Dalit jurist B.R. Ambedkar inscribed these very ideals into India’s supreme law: the Constitution. Yet, the fruits of caste—untouchability, discrimination, and even grave atrocities—continue to circumvent the law. Religious conversion from Hinduism is celebrated by most Dalits as the ultimate anti-caste intervention, but the reincarnation of caste in Buddhist, Christian, Muslim, and Sikh communities proves spiritual rebirth isn’t caste-proof. And while capitalism eroded the old feudal world dominated by caste elites, it simultaneously reproduced new forms of inequity and discrimination. These interventions have no doubt weakened caste, but the parasite has proved durable, adaptable, and unrelenting.

Researcher Alexey Guzey explains, “the moral arc has not been monotonic.” It ebbs and flows in a myriad of ways, usually at unpredictable paces. It indicates rapid progress and immediate regress, even simultaneously. World hunger might plummet while genocides rage, or mass violence declines while social polarization skyrockets. The perceived moral ideals of a population may shift for the better, while its systems behave as amorally or immorally as ever.

Amidst this chaotic set of trends, it remains incumbent on us to pull the moral arc towards justice. Few individuals were more committed to this project than B.R. Ambedkar, who tirelessly worked across domains to redeem Indian society. His work serves as a case study for what is possible—and isn’t—in forging a future free of caste. I explore this in Part 2: One Man’s Moral War.