How do you evaluate the morality of a society? Novelist Fyodor Dostoevsky argued we can judge societies by the quality of their prisons. Echoing the prophetic tradition, philosopher Cornel West references the biblical text of Matthew in his answer: its concern for ‘the least of these.’ Dalit leader Bhimrao Ambedkar joins this choir: “I measure the progress of a community by the degree of progress which women have achieved.”

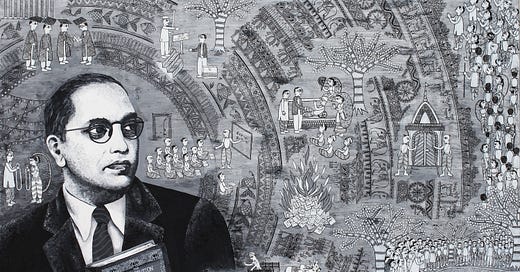

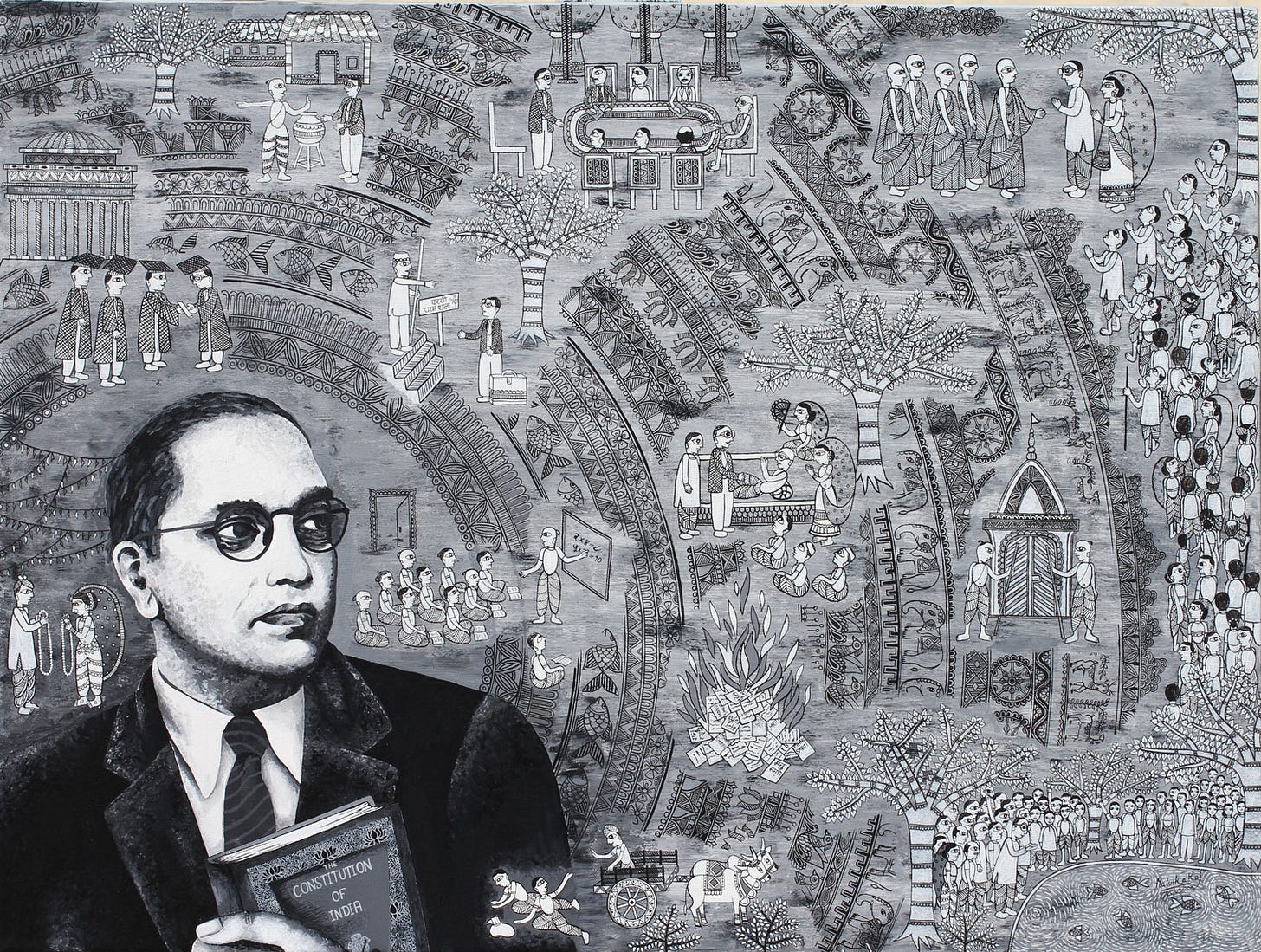

In my last article, I explored the strange and remarkable arc of moral progress throughout history. I believe the moral arc of India is best understood in the life and legacy of a single person: Ambedkar.

Born in 1891 to an “Untouchable” Mahar community in western India, Ambedkar quickly learned about his caste. In school, he was forced to sit in a corner by himself on a burlap cloth so as to not pollute the ground or other students. The school cleaner wouldn’t even touch the cloth. While other students drank openly from the water fountain, he was not allowed to drink unless a “touchable” person—one particular peon, or attendant—would open the fountain for him. “No peon, no water,” he remembers.

Yet it was from this classroom that emerged one of the brightest minds in human history. Ambedkar went on to earn multiple degrees and work as an economist, professor, lawyer, sociologist, founder of multiple political parties, India’s first law minister, and most significantly, chief architect of the Indian Constitution. He led mass movements for Dalit education, Dalit access to public water tanks and temples, worker’s rights, women’s rights, and religious conversion from Hinduism. Across domains of religion, law, politics, media, and economics, Ambedkar restlessly fought for the freedom of the caste-oppressed. His life’s work was to redeem India’s morality from the scourge of caste.

Did he succeed?

Rethinking Dharma

As is appropriate when evaluating political changes, it’s important to measure moral progress relative to a status quo. For much of its history, the status quo of Indian morality was shaped by Brahmanism—an early form of Hinduism that institutionalized the oppression of its lower-made castes.

In this “moral dark age,” as scholar S.S. Raghavachar calls it, the Buddha (5th-4th century BCE) emerged as one of the earliest critics of caste. He reimagined the Brahmanical concept of karma: “Not by birth is one a Brahmin or an outcaste, but by deeds.” He redefined caste categories like “Brahmin” and “outcaste” not as hereditary identities but characteristics one can assume based on their good or bad deeds, respectively. (This seems to me a weak reframing of fundamentally immoral categories—but notions of caste were already deep-rooted in Indian consciousness, and moral alternatives weren’t as accessible.)

Over twenty centuries later, when Ambedkar exhausted nearly every possible legal, political, and social intervention to the problem of caste, he turned eventually to Buddhism. He saw the Buddha’s morality as the lynchpin of moral progress in Indian history—which he summarized as “a mortal conflict between Brahmanism and Buddhism.”

In The Buddha and His Dhamma, Ambedkar writes, “Inequality is the official doctrine of Brahminism. The Buddha opposed it root and branch… [The Buddha’s] Dhamma is morality.” Dhamma, or dharma, is a concept representing cosmic order and moral duty. In the Hindu framework, dharma refers to many moral obligations—including the immoral maintenance of caste distinctions and duties. This contradiction makes it fundamentally unreasonable. Ambedkar calls it an “anti-social morality,” designed to protect narrow group interests at the expense of universal rights.

Conversely, Buddha, Ambedkar, and their followers reimagine the same idea of dharma to uphold alternate virtues—self-cultivation, ethical action, and personal liberation. Ambedkar writes, “Morality [is] to be made sacred and universal. It is to safeguard the growth of the individual.” Similar to how the Christian redefinition of sin was necessary to abolish slavery, this change allowed Indians to retain their beloved, foundational principle of dharma while changing its core obligations.

From Bhakti traditions and Sikhism to Dalit liberation theology and Periyar’s atheism, countless other religious formations and reformations were aimed at redefining social morality. But while conversion and reformation were popular means of moral progress, they had little consequence on a country where nearly 80 percent of people are still Hindu. Moreover, conversion’s mixed record was laid bare by persisting casteism across other religions, including Buddhism, Christianity, Islam, Sikhism, and more.

Constitutional Morality

While celebrated for his religious revelations, Ambedkar’s first attempts at moral progress were grafted into India’s founding document and supreme law: the Constitution. In it, he enshrined his beloved ideals of liberty, equality, and fraternity. He banned untouchability, articulated the equality of all people, prohibited gender discrimination, secured affirmative action and labor rights, and protected freedom of religion—among several other civilizational changes.

These ideals comprised what he called “constitutional morality,” which he argued needed to be embodied in nation-building and culture. Ambedkar writes in Annihilation of Caste: “Constitutional morality is not a natural sentiment. It has to be cultivated. We must realise that our people have yet to learn it. Democracy in India is only a top-dressing on an Indian soil which is essentially undemocratic.” Constitutional morality was not only meant as a set of political interventions, but an antidote for India’s heart.

Law has ‘expressive’ power, in addition to its instrumental functions. It changes the way people think. In the U.S., for example, laws banning discrimination based on sexual orientation were successful not because people feared punishment, but because they authoritatively set the moral and social norms of American society. Laws banning child labor, sexual harassment, and racial discrimination not only penalized once-common behaviors, but fostered broader cultural change to make them seem unthinkable.

Ambedkar seized on this potential for legally induced moral change with a series of 1948 “Hindu code bills” to end the religion’s antiquated treatment of women. The bills were eventually implemented—but only after he resigned in frustration over the government's reluctance in passing them. These bills introduced legal divorce and banned child marriages, granted daughters equal rights to inherit property, gave widows and unmarried daughters equal legal standing in family property, recognized mothers as natural guardians of their children, allowed women to adopt children independently, and required husbands to provide financial maintenance to wives after divorce. In the span of two years, these laws shattered centuries of patriarchal tradition and catalyzed legal reforms in other religious communities, like Islam.

Ambedkar clarifies, however, “rights are not protected by law alone, but by the social and moral conscience of society.” The law influences—but is also subject to—social practice. Despite untouchability’s ban, Dalits continued to face exclusion and segregation in temples, schools, and housing. As recently as 2014, one study found that one in four Indians still practices some form of untouchability in their homes.

Enforcement of the law itself is hardly effective, and even results in its own atrocities. Only a third of reported caste atrocities and rape cases result in convictions. In 2019, the National Campaign Against Torture found that 76 percent of recorded deaths in police custody in India were due to alleged torture or foul play—with 60 percent of victims being from poor and marginalized communities. Similarly, Ambedkar’s legal measures for gender justice have had limited effect, as India still sees some of the highest rates of gender-based violence, including acid attacks, dowry-related murders, and sexual violence. Most tellingly, Dalit women face the disproportionate brunt of this violence.

Ambedkar’s constitutional morality remains articulated, but arrested in development.

The Economics of Dignity

Before he was a guru or jurist, Ambedkar was an economist. Trained in the ivory halls of Colombia University and the London School of Economics, yet fiercely concerned with Dalit misery and the reimagining of Indian society, his economics were, to say the least, complex. He studied under American philosopher and pragmatist John Dewey, who taught him that democracy wasn’t just a form of government, but a form of “associated living”—the opposite of a caste-fractured society.

Today, Ambedkar is claimed by capitalists, socialists, Marxists, communists—and everyone in between. He plants his flag most clearly in States and Minorities, where he argues for state socialism—a planned economy, nationalized industry, and robust labor rights. Ambedkar was principally concerned with the landlessness of Dalits, who were entirely dependent on the employment and wages of upper-caste Hindus. He proposed that all land should be publicly owned and distributed equitably among groups. India’s 1950s and 60s land reforms did abolish the feudal zamindari system in word, but they simply reintroduced loopholes for upper-caste landlords to retain their landholdings.

Today, Dalits constitute 25% of India’s population but own less than 9% of its agricultural land. Dalit scholar Suraj Yengde writes, “This landlessness takes away their legal, official and constitutional validity as the Indian. The [Dalit] community is desperately in need of a second freedom—which must be material freedom, and not merely on paper.” Yengde articulates that moral virtue is not sufficiently inscribed in a nation’s law, but reflected in the material conditions of its people.

As India’s first Labor Minister, Ambedkar championed minimum wages, maternity benefits, and collective bargaining rights. He pioneered the reservation system of affirmative action, which provided Dalits with access to education and government jobs and eventually enabled the emergence of a Dalit middle class. Though these long overdue interventions empowered everyday Indians, they were implemented alongside a suite of Soviet-style socialist policies that slowed India’s economic growth to a staggering halt. In 1991, with just two weeks of foreign reserves left, India embraced capitalism.

In India Calling, writer Anand Giridharadas describes how the American Dream is waning in the States—but remains alive and well in India. Capitalism and its subsequent social changes have ushered in new possibilities for Indians, including Dalits. Journalist Chandra Bhan Prasad writes, “Capitalism is changing caste much faster than any human being… Dalits don’t succeed in villages. Dalits don’t succeed in traditional trades (monopolized by upper castes).” Neoliberal economic policies pushed the needle further in eroding feudal and semi-feudal societies in India, giving Dalits an option to succeed in urban centers.

Ambedkar was wary of free markets, however, noting their record of inequality in the West. His concerns were well-founded. Economic liberalization may have helped some Dalits, but it also helped the source of their agony. A 2017 study found that caste inequality was unimproved—and sometimes worsened—by greater wealth or faster economic growth. Today, Dalits are still relegated to informal, low-wage jobs or marginalized within trades, discriminated against in hiring processes and credit loans, and exploited in a private sector bereft of robust labor laws.

“Caste [is] simultaneously weakened and revived by current economic and political forces,” writes anthropologist David Mosse. Unlike religion or law, markets don’t have intentions. They simply facilitate transactions, however benevolent or harmful the consequences are. Moreover, the centrality of self-interest and money is an unsustainable model for robust, sustainable moral change. Just like his proposal for constitutional morality, Ambedkar rightly predicted that India’s unjust soil would be quicksand for free markets.

As should be quite evident by now, moral progress is neither linear nor guaranteed. Constitutional morality remains codified but incomplete; religious conversion initiates freedom but often reincarnates caste; economic growth begets new opportunities but reifies domination. If the morality of a society is indeed seen in the lives of ‘the least of these,’ India still has far to go.

But Ambedkar’s struggle is not a failure. Today, one and a half billion people inhabit the world of his Constitution, 200 million Dalits walk through doors once closed to them, and over 600 million women enjoy rights he helped secure. Such is the work of a boy once forced to sit on a burlap cloth and only permitted to drink from touchable hands.

The moral arc of history may be long, but as Bhimrao showed, it can be bent.