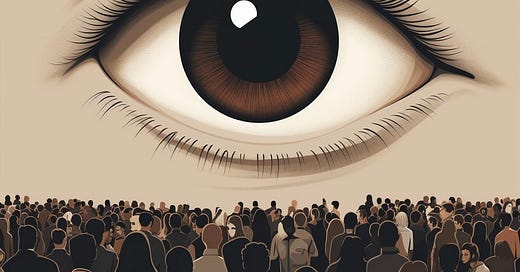

In Intellectuals and Society, the prolific economist Thomas Sowell argued that we don’t hold intellectuals accountable for the results of their ideas—as we do engineers or military commanders. If an engineer’s building plans for a footbridge are faulty, for example, the consequences are dire. Scientific theories can be updated by experimentation. But few ideas are regulated with such scrutiny. Worse—the intelligentsia is insulated from the political consequences of their ideas, which fall disproportionately on vulnerable groups. From free market fables to “wokeness,” many popular social ideas are religiously accepted and transmuted well beyond their original intent. Analysis meant for one use is taken as gospel, coloring parts of reality it was never meant to touch. As a participant in progressive spaces, I often see one such idea taken to irrational extremes: the white gaze.

Novelist Toni Morrison famously conceptualized the white gaze as the reliable assumption that the reader or observer is white—forcing people of color to constantly articulate themselves within a paradigm of whiteness. This observation is profound and often true, but by defending against the “little white man that sits on your shoulder” Morrison described, I worry we’ve recast him into an omnipresent boogeyman haunting all of public life. While critiquing the white gaze, we can’t seem to see ourselves without it. It remains a yardstick for political priorities, a barometer for identity, and a compass for truth. It’s produced illogical and illiberal outcomes—including a shroud for caste apartheid.

“Don’t Fight in Front of White People!”

Marriage counsel, management literature, and street codes share a common proverb: “Defend in public, correct in private.” Politics is no different. Most opinions we encounter are primarily asserted in relation to a broader context, public, or status quo. It’s why minorities avoid airing their own dirty laundry in public—a supposed white audience. Comedian Chris Rock closed his recent special with this idea, which gave him caution during the infamous Oscars slap: “Don’t fight in front of white people!” In progressive politics, this means that as long as the white gaze is present, there are bigger fish to fry (i.e. white supremacy) than alternative issues facing minorities. Intra-group issues are meant to be adjudicated in private, regardless of their scale and severity. But for minorities (often, minorities within minorities) facing entirely non-white problems, this skews the public conversation against us.

When ex-Muslim human rights activists like Yasmine Mohammed or Ayan Hirsi Ali raised genuine concerns about rape culture and patriarchal abuse in their religious communities, progressives slammed them—and by extension, those they advocate for—as Islamophobic. In an interview, Mohammed said: “[Western feminists] consider Muslim women to be of some other species, that they are so different from them. For themselves, they will recognize victim blaming, slut shaming… under Sharia, it’s very, very easy to see a perfect example of rape culture, but for some reason, for ‘those women over there,’ it’s empowering?” Given the white gaze, any critique of minorities is seen as punching down—and we don’t want to punch down, especially in public (in front of white people). But this correction merely gives power back to the white gaze, which retains influence over how people are seen and problems are judged. Herein lies the paradox: the white gaze—whether blindly obeyed or religiously critiqued—constrains people of color to a white paradigm.

Political scientist Yascha Mounk considers this an overuse of an otherwise corrective ‘prism’ of race, gender, and sexual orientation. While avoiding the phrase “cultural Marxism,” he compares this prism to the Marxist tendency to squeeze every historical event into the lens of class—even when alternative variables are more appropriate. Legal scholar Amy Chua confronts similar shortsightedness in the Western export of free market democracy, tracing how the supposed panacea of capitalism and democracy can inadvertently breed ethnic conflict elsewhere. All of this represents Maslow’s law of the instrument: to a hammer, everything looks like a nail. Likewise, this prism projects white/non-white power struggles onto every political interaction everywhere, including where white people aren’t involved. In the Indian context, this prism glosses over an immensely significant axis of power: caste.

Overusing Orientalism

When scholar Edward Said wrote Orientalism, he elucidated centuries of contempt and exploitation. The term described the Western (white) gaze of Eastern societies and cultures, which blindly interpreted and depicted them as barbaric and exotic. Consider something as mainstream as Disney’s 1992 Aladdin, the opening tune of which represents the Middle East as “where they cut off your ear if they don’t like your face, it’s barbaric, but hey, it’s home.” Like Morrison, Said’s coinage was profound—until it became inflated into a theory of everything. So long as any critique of the Eastern world can be attributed to an ambient force of orientalism, then our understanding of facts is woefully constrained.

When the state of California sued Cisco in defense of a Dalit employee in 2020, the Hindu American Foundation argued it was peddling “racist European theories about caste” and enabling “Hinduphobia.” In response to SB 403, a California bill to ban caste discrimination statewide, Republican senators (lobbied by Hindu donors), repeated these complaints, calling the bill language “racist” and “anti-Indian.” When a similar effort commenced in the United Kingdom, one prestigious lawyer alleged that anti-caste policies would perpetuate orientalism. He argued that caste was a Christian myth to malign India, and that reinvigorating the conversation of caste would simply cause further stereotyping and racism towards Indians. In a stellar response, philosopher Meena Dhanda called this “misplaced nativism.”

“Caste or Jati was never benign. It was felt as a burden to be overthrown. A precursor of Ambedkar, Jotiba Phule (1826–1890), decried the caste system as ‘the code of crude and inhuman laws to which we can find no parallel among other nations’… This part of our pre-colonial history also shows that ideas of equality stirred the minds of Indians well before the colonial encounter and did not spring for the first time from Christian missionary activities… The [lawyer’s] nativism is misplaced for the further reason that he underestimates the cultural resources of the Indic civilization—whilst spawning inequality it also produced elements of an antidote.”

Those crying racism when addressing caste are purporting a patently false, manipulated history—one that does not engage realistically with our checkered past. And it’s a story that is easily accepted by Western liberals, because of our ideological heuristics. We presume that critique of the East is probably orientalist, that terrible social arrangements like caste are functions of colonialism, and that the factor of race remains more salient than any other. I actually think the postmodernist intellectuals behind these assumptions— Foucault, Spivak, Said, and others—were quite careful and clear-eyed in their analysis. It’s the downstream exaggeration of their ideas that makes them powerfully misleading. While the idea of the white gaze is useful in many arenas, it can hinder our ethical convictions from scaling with the true nature and magnitude of problems.

The Limits of Brownness

When Savarnas (upper castes or dominant castes) appeal to the white gaze to obscure or minimize the realities of caste, they cite their racial location of “brownness,” which situates them closer to the bottom of America’s racial caste hierarchy and awards them progressive sympathies. By foregrounding the issue of caste, I’ve been personally accused of depicting a barbaric, backwards image of India, which Savarnas fear feeds into an orientalist, white gaze. But the problem of the white gaze is surely less important than the slow genocide of Dalits and Indian Muslims and Christians—isn’t it?

In her book The Trauma of Caste, Dalit activist Thenmozhi Soundarajan levies a scathing critique to the South Asian American embrace of a “brown” identity: “It is a false mono-narrative of South Asianness that serves only to perpetuate the violence of caste and other historic traumas while providing new terrain for exploitation and discrimination for us as South Asian Americans… In embracing brownness as the key identity, they make their privileged positions of caste, class, immigration, and race—which would situate them in a position of not only oppression but also privilege—much harder to interrogate.”

Race and racialization is a deeply pervasive social fiction, and South Asian Americans aren’t spared under it. But it’s merely one way to understand their experience—and increasingly, a less salient one. By furiously accounting for the white gaze, we actually become captive to it. This is why the popular “brown” cause aims no further than to make white people say “Chai,” instead of “Chai tea.” That’s our trademark ‘struggle.’ There’s much to say here—at the risk of ranting—but this is an understated fact: the Dalit struggle, in truth, has little to do with white people. Caste was not created by white people and caste is not perpetuated by white people. It is the primary social power struggle of Indian communities everywhere. For the American Left, these are uncomfortable facts. But unless we are willing to peer beyond our ideological blinders, we will never experience an honest engagement with many important issues. Worse—we will forsake many who suffer in the dark.

Reminds me of the salad bowl vs melting pot theory of assimilation debate

This piece was so so insightful. "Those crying racism when addressing caste are purporting a patently false, manipulated history—one that does not engage realistically with our checkered past. "